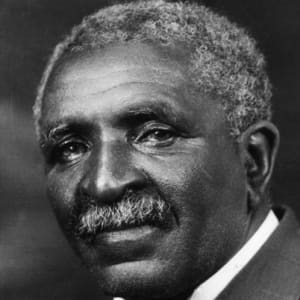

You

have probably heard of George Washington Carver (1864-1943) as the

early-twentieth-century Peanut Man who developed hundreds of commercial

products from peanuts, and from other southern United States crops, in his

laboratory at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. But these products were probably

the least important part of his work, at that time and in his legacy today. He

is also remembered as the black man who earned respect from whites who might

otherwise have dismissed blacks as an inferior, perhaps uneducable, race. I

have recently posted a video about Carver, filmed at his birthplace.

Carver

had a brilliant mind for botany and chemistry. He was also a teacher whom his

students loved, because he was humble despite his vast knowledge, and he cared

individually about each student. He wanted each student to experience

scientific discovery for themselves. While most science teachers today take

this approach, it was uncommon in Carver’s day.

The

fame was as much for his personal story as for his scientific work. He was born

into slavery just before the end of the Civil War, then kidnapped. His owner

got him back in exchange for a horse. After the war, George’s owner raised him

as one of his own children. He struggled for years to get an education from

whatever school would allow a black man to learn. He was the only black student

at Iowa State University. His mentors there wanted him to stay as a faculty

member, but instead he accepted a call from Booker T. Washington to join the

Tuskegee faculty.

For

much of his career, Carver labored in obscurity. Tuskegee president Booker T.

Washington was impatient with Carver’s disorganized approach to college duties.

Whenever Carver accomplished more, Booker T. Washington always thought of

something more that he ordered Carver to do. At one point, even though Carver

spent every waking moment working for the institute, Washington told Carver he

needed to repair the bathrooms. Washington’s regimented and disciplined

approach to everything conflicted with Carver’s slower and more thoughtful

approach.

Then

in 1921, Carver testified before the federal House Ways and Means Committee

about all the food and industrial products that could be made from peanuts. The

committee was interested because World War I had interrupted many imports into

the United States, and they wanted to know what “home-grown” products we could

have in the event of a future war. Even though these products ended up not

being marketed, the committee was very impressed with this humble and brilliant

man. From that point, Carver became a celebrity, and his fame spread worldwide.

Once

at Tuskegee, Carver showed his ability to produce excellent work with almost no

resources. Though he eventually had a lot of glassware for his teaching and

research laboratories, he had literally nothing to work with when he first

arrived. So, he found a whiskey bottle at the dump. He tied a string around the

middle. He cooled the bottle in cold water, then lit the string on fire. The

fire made the cold bottle crack in two. The top half was a funnel, the bottom

half a beaker.

By

the end of his life, Carver was receiving many prizes and worldwide

recognition. Meanwhile, in American society, the legal rights for black people

were becoming ever more restricted. After an initial period of openness after

the Civil War, southern states found ways to prevent blacks from voting, and

they ended up with almost no political voice. While Booker T. Washington and

George Washington Carver were widely admired, most white people considered them

individual exceptions from their otherwise benighted race.

Max

Otto (see previous essay) quoted Russell Lord’s “deeply disturbing” book Behold

Our Land. Lord wrote about the soil erosion, which ruined the livelihoods

of poor farmers, that was going on “under the eye of a teaching and research

staff of considerable distinction; and yet it all was, and is, by them

completely ignored. They go right on teaching their geology, their botany,

their zoology, their chemistry and physics, their archaeology, their Greek and

Latin and English, with no thought or mention of the tragic transformation of

the good green country roundabout.” Maybe Lord referred to the major

universities, but George Washington Carver was the exact opposite of this

disconnected academic lassitude.

Carver

never sought fame (though it came to him) or fortune (which he had

opportunities to refuse). He lived in a small room on the Tuskegee campus.

Books were stacked floor to ceiling in the corner. He had a display case for

his crochet work. Rocks and stalactites covered a table, and flowers crowded

his window box. His personal space reminds me of my own.

I

chose George Washington Carver as my favorite scientist in my recent book. The main reason was not so much because of his scientific research,

which was creative but not of the highest quality, as for his motivation. He

believed that scientific research at a university should prove directly helpful

to the people living around it, and to the world in general. The inspiration of

his peanut research (and also research on sweet potatoes and pecans) was to

allow poor farmers to produce value-added products, at home, that they could

sell for more money than peanuts. He also did research, and taught local

farmers, about how to preserve soil fertility, so that they could produce more

from each of their acres. This is also one of my main motivations in teaching

and research. Like Carver, I am a mediocre scientific researcher, but my heart

is in outreach to the wider community, opening their eyes to the wonders and

practical benefits of science.

All

this, despite the fact that Carver did not really follow what nearly every

scientist in his day and today would consider good scientific method. That is

the topic of the next essay.